Curatorial Statement

While social technologies and corporate AI neural networks – think Siri or Alexa – epitomise the exploitation of desire and emotions, they fail at fostering the empathy characteristic for authentic human connections. These seemingly symbiotic relationships between humans and networked non-humans signal a future that questions its own ability to reimagine existing power structures, and the social and emotional systems within them.

Looking beyond accounts of ‘tech-obsessed’, ‘sociopathic millennials’ demonstrates how the urgency for an empathetic experience emerges within societal polarisation and accelerationist Silicon Valley mentality. Intertwined in a web of computationally mediated relationships, Empathy Loading speculates on the future of feeling, and explores the role empathy can play in how humans shape, cohabit and nurture their relationships with machines.

Complicating these emotional connections is at the centre of the work by Friendred, Elisa Giardina Papa, Vishal Kumaraswamy and Marie-Eve Levasseur, who each submitted a creative ‘proposition’ for the project. Acting as unfinished sketches, these artworks reflect upon the interweaving of the synthetic and organic worlds, and the emergence of new forms of caretaking and caregiving. Each of the propositions takes a distinct form, and while some of them incorporate already materialised ideas from the artists’ previous works, others have embarked on an entirely new research path. Opening new channels of dialogue and inviting artists to investigate experimentative threads the curators encouraged approaches that were focused on the process rather and less oriented toward the final result.

As Friendred demonstrates in Decisions (2020), openness to new forms of relationships with networked non-humans can result in unexpected ‘intra-actions’ between assemblages of organic and synthetic cognition. In #algofeels (2020), Vishal Kumaraswamy questions the positive outcome of the intertwining of human and non-human intelligence and explores this alien potency for sentience and perception of self-awareness. Marie-Eve Levasseur’s surface 4.0 (chromatic chatter no.2) (2020) proposes new ways of feeling with others and speculates on the role of sensorial intelligence in creating a more-than-human future. Elisa Giardina Papa reframes the questions of empathy through the lens of precarious emotional labour in Bot? Virtual Boyfriend/Girlfriend (2016), a work that the artist has revisited for Empathy Loading.

In the main commission, Vishal Kumaraswamy expands on ideas in his proposition and constructs narrative frameworks exploring the emotional intelligence of AI, raising questions about the ethics of designing sentient algorithms. He contemplates the entanglement of computation and cognition, re-imagining desire from the machine’s perspective.

Empathy Loading is an online project consisting of two sections. One includes artworks commissioned for the project in response to the curatorial themes: they include creative ‘propositions’, the main commission, and information about the public events accompanying the project, as well as a conversation between Vishal Kumaraswamy and Zarina Muhammad and a speculative listening workshop led by Amina Abbas-Nazari. The other section, Reading Room, features a commissioned text by Allison Parrish and a reference list used by the curatorial team.

The multitude of artistic approaches explored through this project is testament to the artists’ refusal to follow techno-capitalist visions of the future, and to apply their critical evaluation skills to the present in order to positively influence the futures of human and non-human cohabitation. Empathy Loading is a vehicle to unite, separate and subvert the hierarchies in technology, which stem from human biases and reimagine their prospective emotional relationships.

1. A Reflection: By Allison Parrish

2. Artists Q&As: Friendred

3. Artists Q&As: Vishal Kumaraswamy

4. Artists Q&As: Marie-Eve Levasseur

5. Artists Q&As: Elisa Giardina Papa

6. References

7. Supported By

8. Curated By

A Reflection, 2020

Allison Parrish

'Narcissus... the water represents you exactly as you are when you gaze upon it. [...] Do you then expect the pool to enter into conversation with you?'

– Philostratus the Elder

First marriage. A magic mirror referred the Magic Mirror first appeared. The Magic Mirror also appeared the Magic Mirror always told the Evil Queen that she was the fairest one of all.

Namely that she was filled with grace from the very varies with wavelength, so will the refraction angle as light goes from one to the focal length of a converging lens. Is the focal length of the lens. Changes with the focal length of the lens. Of the camera to the focal length of the lens: reciprocal of the focal length of the camera lens; equal to the reciprocal of the focal length measured in metres; with a positive focal length overcomes singlet emission. Dye lasers with an external. Dye lasers use an organic dye as the gain medium.

Because the liquid medium of a dye because the gain medium of a disk. The size of such a disk Etalon is given by ) occurs when the optical path shifts. If the optical path length variations are more than a wavelength generally produce light over a wavelength range over a significant wavelength range. There are many types and categories of tunable lasers. They exist in the gas, is carried out as "secondary", is dealing with only defleshed bones...

Author’s Note

I wrote this piece using a series of computer programs. First, I created a corpus from the text of every English Wikipedia page linked from the page for Mirror, breaking those texts into smaller segments using a neural network trained on poetic line breaks. A separate procedure repeatedly appends text segments drawn from this corpus to its output, picking the segment that is most similar to the previous segment, until the specified number of segments has been reached. Similarity between segments is ascertained using several different metrics: semantic similarity (using GloVe vectors), conversational similarity (i.e., semantic similarity based on preceding context), and phonetic similarity. I generated several different candidates using this process and picked the one I liked best, but I did not make any internal edits to the text of the piece.

This text is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license.

Allison Parrish

Brooklyn, New York

June 2020

A Reflection was originally commissioned for Empathy Loading.

Allison Parrish

Allison Parrish is a computer programmer, poet, educator and game designer whose teaching and practice address the unusual phenomena that blossom when language and computers meet, with a focus on artificial intelligence and computational creativity. She is an Assistant Arts Professor at NYU's Interactive Telecommunications Program, where she gained her Master's degree in 2008. Named Best Maker of Poetry Bots by the Village Voice in 2016, Allison’s computer-generated poetry has recently been published in Ninth Letter and Vetch. Her first full-length book of computer-generated poetry, Articulations, was published by Counterpath in 2018.

Artists Q&As: Friendred

EL: Non-human cognition is a recurring theme in your practice. In Skin-awareness II (2019), you explored how sensorial capacities of humans can be extended through movement and interaction with digital technologies. Do you think it is possible to identify similar potential in emotional relationships between humans and networked non-humans? What might that look like?

F: The level of interaction among human and machine in my previous work, Skin-awareness II (2019) was emotional to a certain extent. The sensorial environment consisted of a technological medium that took the role of a third choreographer, challenging the authorship of movements.

EL: What are your thoughts on the fact that human empathy is a product of chemical reactions to outside stimuli and machine empathy is a result of programming, introducing hierarchical relationships between humans and networked non-humans, where one iteration of empathy is considered more real? Or is it something else?

F: It’s a really fascinating question, but it depends on what you really define as empathy. If empathy is, as you say, simply responses to environmental stimuli, then machines are able to exhibit empathy. Intra-action between human and machine makes up a lot of the basis of my work, the input from the human participant to the machine algorithms and the consequent output of the machine could be construed as a form of machine empathy, a mirroring of humans’ traits. Neurons in the brain are also considered by some as a computational unit, although complex, the brain could function in a similar fashion to a computer. Therefore, as machines become more complex it is possible for a truer form of machine empathy to materialise.

EL: Do humans have an ethical responsibility to care for networked non-humans and is it a mutual responsibility? What might this look like?

F: As we rely more and more on the functions of networked non-humans for every aspect of our lives, the care we provide for them becomes progressively important. The type of care we provide for these networked non-humans manifests as the constant updating and maintenance of ubiquitous computer technology and the integration of these technologies into our society.

EL: As part of the project, the curators invited you to respond to a brief and come up with a ‘creative proposition’. How did this process of creating a ‘teaser’ for a work feel to you in comparison to creating a finished work?

F: Although shorter, the feeling is very similar to me. To create a ‘teaser’ like this, I must first have a concept of the finished work, fully fleshed out, otherwise, the snapshot I provide would have no meaning.

EL: From our conversations, we know that your work involves more than simply using technology as a tool. You talk about collaborating with machines. How do you balance the subtle nuances of communication and chance when collaborating with increasingly sentient technology?

F: I believe technology is more than just a tool; it’s situated, sentient and poetic. In various situations, especially where human and machine act together, technology inspires people to react subjectively and facilitates communication through more diverse mediums than the speech and body language we possess as humans in order to communicate. As technology becomes more sentient, the potential for its use in the expansion of communicative ability is also elaborated.

EL: Is there a particular moment when collaboration takes place between yourself and the AI?

F: During the performances I design, the collaboration is a continuum that begins at the start of the piece. The piece is never complete without the feedback loops created between performer and machine.

EL: How could the creation of alternate topologies by networked non-humans in Decisions (2020) act as a site for the formation of new relationships between humans and technology?

F: Decisions (2020) was created from a similar perspective on human-machine communication to my previous work, but represents a different form of output in comparison to the installations previously used. The topologies created are the representation of the algorithmic ‘empathy’, visual feedback of human-directed inputs to the machine, and allows for decisions within the system to be a collaborative effort between participants, both human and non-human.

EL: Can you describe what drew you to the textures of geographical structures, such as clouds and stalactites, when considering the empathetic relationships with machines?

F: The dynamic natural forms created by Clouds, Mist and Stalactites (2020) allow for very malleable outputs, creating more complex representations of the inputs provided. Influences from nature are always at the forefront of my mind when creating, especially aesthetically. The fusion of natural aesthetics with algorithmic machine-centric inner workings exemplifies the intertwined relationship between living beings and machines that my work aims to emphasise.

EL: One of your main premises for producing this proposition was that it was experimental, with an unknown outcome. Could you elaborate on how the process of intra-action influenced you to explore the ways in which systems of mutual care can manifest?

F: The true basis of mutual care in nature is based on a foundation of shared empathy, so without the design of empathetic machines, an effective system of mutual care between human and machine could not exist. This piece aimed to explore one aspect of shared empathy by forming a collaboration between machine and human, with human input and image-based machine feedback as the basis of communication. Further design of strategies for human-computer communication and shared empathy will be key for the creation of systems of mutual care.

Artists Q&As: Vishal Kumaraswamy

EL: The line of enquiry into the ‘sentience of the Internet’ and of artificial intelligence within neural networks is a recurring theme throughout your practice. It can be seen in #algorithmictruth (2016-2018) as you ponder digital intimacy and speculate on teenage angst exhibited by virtual beings and look towards the future of these interspecies relationships. What has influenced your practice and motivated you to look around and think about how we relate to non-humans?

VK: My inquiries into the sentience of the Internet stem from a personal incident in early 2015. I was in the process of applying to art schools and during a period of frenetic document review the machine I was working on crashed. My attempts to revive my data or the machine itself failed and I missed the deadlines for some of the applications. Strangely enough, three days after I’d missed my chance to apply, I was able to restart the computer and see that all of my data was intact. This led me to joking about this machine having a mind of its own as the applications I was writing were exceptionally bad, and I would not have been successful . Every time I narrated this incident to friends, they joked about my imagination running wild and I began to think about it as a potential film that I would like to develop. It was not until the end of that year, after reading some continental philosophy and immersing myself in the environment of an art school, that I was able to substantiate for myself that this was a line of enquiry I wanted to follow. It was basically a way for me to bridge real-life experiences; the various pieces of technology I’d used as a concert photographer, film-maker and motorcycle traveller with some of the critical theory I was reading. It was my attachment to these devices and objects; camera equipment, motorcycles etc., that really led me to examine my relationship with the internet.

EL: Do humans have an ethical responsibility to care for networked non-humans and is it a mutual responsibility? What might this look like?

VK: I think as humans we constantly wrestle with the idea of creation and the responsibility of care for that creation. The act of forming bonds with inanimate objects creates a state of emotional entanglement and this is amplified with networked non-humans and devices. The morality of this relationship is open to interpretation, especially if we’re going to model our responsibility towards machines on existing models of care between humans. It is also problematic, as care between humans is constantly commodified and the language of care becomes one of money. But, if we are going to consider the extent of our responsibility towards machines, we can only draw from socialist principles and realise that our individual actions influence the behaviour of other users within this networked space. The sooner we embrace the idea that we share this space and cannot possibly claim it only for ourselves, the forms of care will become organic as we assume individual responsibility towards a shared future.

EL: The way you employ narrative and introspective conversations within your work seems to play a significant role. What is the significance of speculative fiction in your practice and how does it influence the narratives you devise?

VK: Reflection and introspection are certainly important notions within my works. It is rooted in my own personal meditative practices, which by themselves are often influenced by seemingly simple interactions that have had a delayed effect on me. The narratives are thus tangential possibilities of real-life incidents, but I move the perspectives around to engage with things I’m thinking about at that point in time. In a way, I think speculating on multiple outcomes of specific events allows me to keep the work rooted in reality.

EL: The concept of freedom seems to be a crucial part of your practice. In the write up for Azaadi, Meherbaani Se (2018-19) you ask ‘When Dystopia portrays itself as a false utopia, is there really any hope?’ Could you elaborate on this question with regards to the future you envisage for virtual beings and what freedom would mean in such a scenario?

VK: If we think about freedom as a concept, we think about personal and individual freedoms. Within the neoliberal societies that we inhabit, the pursuit of this form of freedom often comes at the cost of surrendering some of our rights and is not absolute. It is commodified as we enter into contracts with the state, corporations and in turn with each other with freedom only occurring in transactional modes. But when we imagine the forms of freedom for networked beings, we must think in the language of autonomy. The more we think about it as a binary model between humans and machines, we run the risk of forcing machines into a hierarchy, one that might not end well.

EL: What in particular has influenced your practice to look at these human, non-human relationships in such a way and made you think about how both participants are affected by these connections? Were there any particular artists’ practices, theories and influences crucial to making of this work?

VK: I began looking closely at networked devices and their impact on our behaviour sometime around late 2012 as 3G became ubiquitous in India. WhatsApp became the default text messaging app, as a large section of the country went online for the first time, including my mother who had barely accessed the web on a computer. Attempting to navigate smartphone interfaces and operating systems was a regular source of anxiety, particularly as navigating mobile devices followed set behavioural patterns that were first learned on a personal computer. For someone who didn’t possess muscle memory or understand the language of user interface, this was extremely difficult and using the phone triggered anger and anxiety. This has not become easier over the years and the user experience for older or disabled technology users are still unintuitive and problematic. This strained relationship between the user and the device forms the basis for speculation in some of my works.

I’m currently looking at the gendering of AI, the emotional intelligence of AI algorithms and I’ve been looking at the research of Maya Indira Ganesh’s including her recent essay 'Between Flesh: Tech Degrees of Separation',Contagious Architecture (2013) by Luciana Parisi, and the Buddhist principles relating to autonomy of the self.

Some of the works that I was thinking about are Ian Cheng’s Emissaries (2015-17), Morehshin Allahyari’s She Who Sees The Unknown (2016-), Keiken’s Feel My Metaverse (2019), Stephanie Dinkin’s Not The Only One [N’TOO](2017), Sougwen Chung’s Drawing Operations (2015-) series and Yuri Pattison’s user-space (2016).

EL: As part of the project, the curators invited you to respond to a brief and work creatively towards the development of a proposition. How did this experience of creating a ‘teaser’ for a work feel to you in comparison to creating a finished piece?

VK: I approached the proposition as an outlet for the first stage of my research, as an opportunity to present it in practice. It was serendipitous that I was able to directly relate to the themes of the brief. I looked at it as a chapter of a longer work that I intended to expand on at a later time.

EL: In our previous discussions regarding #algofeels we touched upon the difference between human desire and sentience as opposed to machine desire. Looking at how in the proposition these two threads intertwine and blur, what according to you is the root of this disjuncture? Could these differences be put aside towards the realisation of freedom you signify as being the shared trait amongst the two?

VK: In the early stages of my research into machine intelligence and the nature of sentience, I held strong beliefs regarding the notion of ‘Technological Singularity’, the idea that technology will surpass humanity and that human and machine intelligence will merge to form a single being. But ascribing emotional traits to machines, first as a speculative practice and later to inform how we innovate, blurs this difference. I feel that implementing emotionally supportive, diverse infrastructures within which these AI algorithms are programmed can lead us towards developing inclusive models of machine intelligence. Without this, we will continue to have Western-centric, Eurocentric algorithms that perpetuate existing racial and social biases and aren’t catering to the majority of the world’s population. I feel that exercising care and empathy at the stage of programming will refocus our imagination towards machine desire, that should be modelled after a duty of care instead of ruthlessly pursuing task-completion and efficiency.

EL: It seems that in your work, you consider the ability to introspect to be a crucial trait for sentience to exist. In one of the scenes in #algofeels, the machine conversing with a repair technician pours through its datasets in attempt to locate commonalities between them both. Could you elaborate on why the machine acts this way and what necessitates this need for non-humans to locate these shared traits?

VK: When we speak of sentience in living beings, we find the need to differentiate between human sentience and that of other organisms such as plants or animals. We have evidence that forests contain underground neural networks and animals have long been able to communicate with humans using a variety of recognisable signals and actions. So, sentience as a trait is not exclusive to us but the way in which we express and perceive it might be. When imagining sentience in machines, the closest possible evidence of emotion can be expressed as a series of intelligent malfunctions. The act of being able to divert computing power to present an action as deliberate can be understood as an attempt at self-determination. I think the ability to discern between logical actions and programmed malfunctions might be the way we understand machine sentience.

Above Image: Vishal Kumaraswamy, #algorithmictruth, 2016-2018, film still, ©️image courtesy of the artist

Artists Q&As: Marie-Eve Levasseur

EL: Non-human cognition is a recurring theme in your practice. In A Chatroom Fabulation (2017-18), you developed a fictional cross-species dialogue between humans, plants and algorithms, set in cyberspace. What influenced your practice to look around and think about how we relate to non-humans?

MEL: I think that a certain desire to connect is something quite universal across species. Even plants connect, exchanging chemical messages through the air, or communicating with their roots underneath the earth. To understand other living beings, there is a need to find a common language through which we share perspectives, ideas and affects. Some years ago, I came upon a science-fiction novel by Naomi Mitchison, Memoirs of a Spacewoman (1962), which offers a powerful insight on empathy and care, on this need to connect with and understand other species. In humans, we have different languages (or codes if you prefer), we have mediating devices (like our 💻 and 📱) and we have our bodies 💪. This is what I know. The freedom that I have in order to interpret the codes (or the bodies) is mine (just call it subjectivity). I find this potential for misunderstandings fascinating. When I moved from Canada to Germany, I found myself navigating in another language (even another body language) and my screen space grew more important in keeping a connection with people in Montreal. That is when I started to include the technological factor more seriously in the communication equation. Also, reading Donna J. Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble (2016) made me shift my perspective, trying to include others in this multi-species configuration and acknowledging the inherent interdependence between living beings themselves, as well as with technological others in this world. A post-human world has to be post-anthropocentric too. So this quest for a way to communicate with each other and develop multiple perspectives has always been involved in my work.

EL: One of the main premises of the project was to expand the understanding of cohabitation with networked non-humans. What influenced your research and creative process while making the work and which events/situations inspired you?

MEL: Many things. Of course, me living abroad and relying on my screens for connection with home intensified my experience of networked non-humans as extensions and facilitators for efficient communication. This could be seen as a first trigger. I often feed on previous works and external research to start brainstorming. So the inspiration to imagine a communication technology that would function as a wearable augmentation of the body lies in late technological developments, in feminist science-fiction, media theory and philosophy. The idea of technology as a prosthesis of some sort to optimise the incomplete human body was reinforced by Karin Harrasser with her book Körper 2.0: Über die technische Erweiterbarkeit des Menschen (2013). Some research and personal experiences with online dating also helped focus my work on what an intimate connection through a screen could look like. Les sentiments du capitalisme (2007) by Eva Illouz helped me confirm my own feelings on the difficulty to express affects with words in the absence of the physical body (that is, without touch, smell, etc.) So I imagined a second skin that could offer protection (even against viruses), allowing the surface to change colour and texture like the skin of an 🐙 would (so that we too, could communicate chromatically). The second skin would optimise intimacy and empathy by remotely giving tactile sensation to the user. It would also optimise learning processes and allow a body to feel what another body feels. Some elements in science-fiction stories like Woman on the Edge of Time (1976) by Marge Piercy and Gotta Sing Gotta Dance (1978) by John Varley inspired me to think the device as a sustainable one, that is organic based, symbiotic, biodegradable and temporary.

EL: The organic and synthetic matter operate in different systems of knowledge. In your work, you often blend the two and engage with both human and non-human ecologies. What have you learnt from engaging with non-human ecosystems?

MEL: I have observed how we relate to others through technology and how this affects interactions and intimacies. I have also learnt to think of the concept of humanity as including technological others 🤖 (thanks to philosopher Rosi Braidotti). They are so near to our bodies that we almost cannot separate them from us any more. Implants are not necessary: we are all cyborgs already. Therefore, I think it is an interesting exercise to render technology in a more organic way. It reminds us of a certain fragility and prepares us for empathy. There is a great mutual dependency, between humans and the tools they use and love for what they provide and optimise. Non-human ecosystems have been programmed for a purpose and as long as they fulfil it, they are considered useful and are taken care of. In a capitalist system, non-functional beings are not useful. It makes us, humans and non-humans, disposable. So one thing I wish we’d keep in mind along the way, is that our organic bodies should be taken care of and respected, even if not considered ‘useful’ any more or at all – by whatever capitalist criteria society decided. And I like to think that empathy stays in the continuously updating definition of humanity.

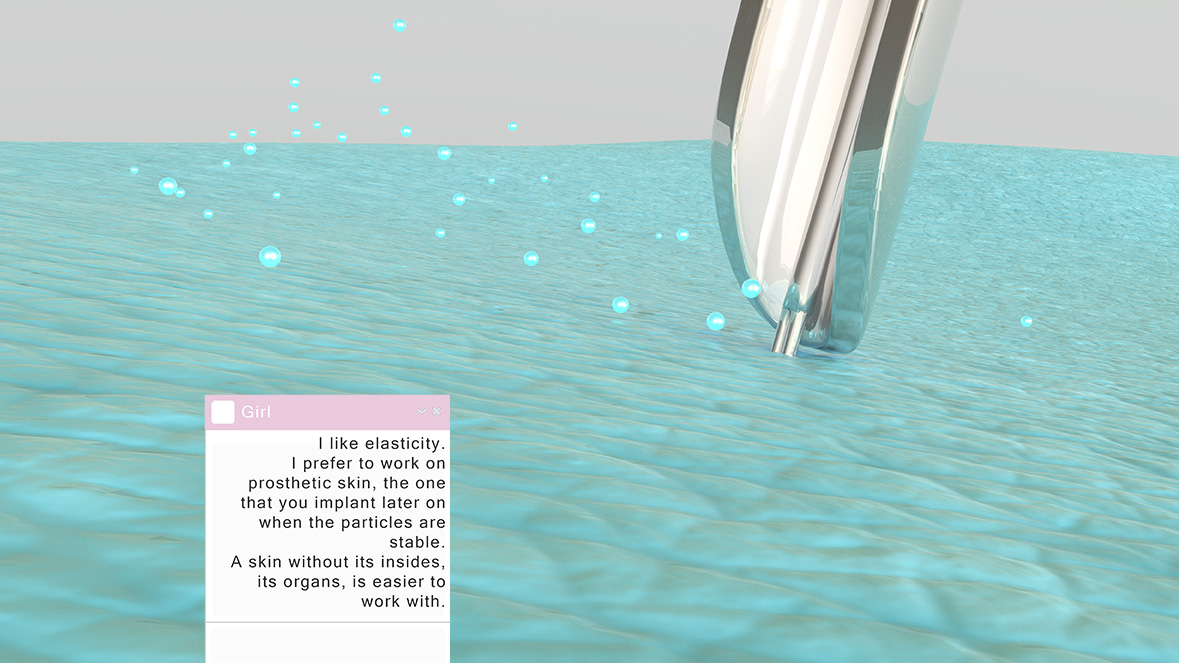

EL: surface 4.0 (chromatic chatter no.2) (2020) presents the symbiotic extension as a device that would allow the wearer to escape ‘definition, meaning, categorisation’ and effectively detach themselves from their own identity. What makes these qualities significant in the context of the work?

MEL: It is more the formation of a singular identity that I find crucial here. With the chromatic way of communicating that the device would allow, I imagine a potential to escape the weight of defining words and to open the possibility of a new language based on iridescent colours, patterns and textures. Given that we wear that second skin device, every individual would be able to choose a different skin colour 🌈 and let it evolve with their sensations. It would result in a multitude of skin tones and patterns, constantly changing, showing the diversity of our becomings. I see the concept of difference here in a Deleuzian sense, as generative and inspirational, a multiplicity that stands for positive emancipation. Some affects and feelings are not easy to categorise or explain. There are parameters for which it is difficult to write a computer program. These are not easily quantifiable, but might be easier to express in colours and patterns, and I think technology can help us achieve that.

EL: Do humans have an ethical responsibility to care for networked non-humans and is it a mutual responsibility? What might this look like?

MEL: I think the responsibility is given by us and above all, by the world we share with other species. We definitely have a responsibility to care for a sustainable way of working with technologies; repairable, recyclable, or biodegradable technologies that are accessible for all to use. This is the responsibility that we should have in mind when thinking and producing new technologies.

EL: As an additional element to the film you sent us an AR filter. What’s the relationship between it and the proposition? Would you say that this is the current technologically feasible version of it?

MEL: Working in the field of media art, I follow technological developments. It informs my work, but I’m still a bit far away from the labs where it actually occurs (for now). There might be already wearable textile-based technologies enhancing tactility and coming near to the science-fiction I imagined. But yes, one could say the AR face filter is a technology that is available to me as the first visualisation of it.

EL: As part of the project, the curators invited you to respond to a brief and come up with a ‘creative proposition’. How did this process of creating a ‘teaser’ for a work feel to you in comparison to creating a finished work?

MEL: I liked the idea of providing an unfinished work, an input to contribute to a bigger conversation. It definitely gave me the opportunity to restructure my perspective, develop certain aspects of a new science-fiction narrative I was working on and see it integrated in an exciting project. Although I am not used to working super fast, I tried to condense the ideas I had in a form that gives an impression of what it could become. Looking forward to seeing the project online!

Above Image: Marie-Eve Levasseur, An Inverted System to Feel (your shared agenda), 2016, 3D animation still, ©️image courtesy of the artist

Artists Q&As: Elisa Giardina Papa

EL: In your work Technologies of Care (2016) you interviewed digital caregivers, alongside documenting your ‘affair’ with an interactive chatbot. Could you elaborate on this experience of interacting with outsourced affective labourers?

EGP: I started the research for Technologies of Care (2016) after talking with a friend in Sicily who had recently started to work as an online micro labourer. She was doing short translations – English to Italian – but had also begun to experiment with some gigs based on private online chats. She would speak in Italian twice a week at night with one client from the UK to aid his sleep. That’s how I began to investigate the economics and politics of digitally outsourced care and affective labour. I got in touch with several other workers online. I had conversations with an Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR) artist, an online dating coach, a fetish video performer and fairy tale author, a social media fan-for-hire, a nail wrap designer, and a customer service operator, among others. Based in Brazil, Greece, the Philippines, Venezuela, and the United States, they worked as anonymous freelancers, connected via outsourcing platforms to customers mainly located in the US, the UK, and Canada. In the work logs, I also included online conversations I had with chatbots that reproduce emotional labour – algorithms programmed to simulate emotional intelligence. One of the stories – Worker 7 – Bot? Virtual Boyfriend/Girlfriend – is based on a three-month-long text-based interaction with the chatbot called the ‘Invisible Boyfriend’. I didn’t know it at the time, but the app I subscribed to only began as a chatbot service. Later, when the founders determined that it wasn’t convincing enough, they switched to outsourced gig workers – freelance writers. So when I was exchanging texts with the ‘Invisible Boyfriend’, I was actually connecting with approximately 600 writers (micro-task workers) who would interchangeably partner with my account to enable the fantasy of this tireless companion and love giver.

EL: In your practice, you often explore the themes of digital care and labour and the ways in which they are transformed through increasing automation. While our most emotional interactions are often mediated digitally by corporations, do you think that these connections can still retain intimacy?

EGP: Regarding how care and labour have been transformed by automation – and digital economies more broadly – I am actually trying to focus on what has not been transformed, what hasn’t changed. That is, I try to trace how pre-existing inequalities in care labour – the feminisation of caregiving, paired with its lack of recognition as waged work, and likewise the historical colonial division of labour between the Global North and Global South – have been both exacerbated and obscured by techno-capitalism. The ways in which care and affective work is still enmeshed in historical structures of patriarchal, colonial and racial capitalism is, for example, clearly diagnosed in Neda Atanasoski and Kalindi Vora’s Surrogate Humanity: Race, Robots, and the Politics of Technological Futures (2019).

EL: Most stories in Technologies of Care (2016) are told with a monotone female English accent, sometimes the differences between the interviewer and the interviewee blur. What was the reasoning behind this artistic choice? What does this nuance add to the work itself and the way in which it is perceived by the viewer?

EGP: Each story starts with a voice in the worker’s native language, but then quickly fades into a standard American English. I made this choice to protect the privacy of the workers, while at the same time hinting at the processes of abstraction, standardisation, and invisibilisation that the gig economy imposes upon its labourers. When I started Technologies of Care (2016), the first woman I talked to – after my friend in Sicily – was a Biology professor from Venezuela with a Master’s degree in Immunology and a PhD in Biochemistry. After we spoke, she decided to participate in the project, and she also asked to remain anonymous; this request set the parameters for the entire piece. She also recounted how she worked as a team with her daughter under a single male-identified profile for several gig-economy platforms. Among other services, she was ghostwriting homework for high-school students, most of whom were located in the United States. She intentionally used a male profile to circumvent gender wage devaluation, stating: ‘I work in academia, I am no stranger to the wage gap and heteronormativity in our society. I am sure that women make less than their male counterparts for the same work, and I am also Latin American. Being a Latina woman makes me more prone to receiving less for the same hard work.’ The gig economy abstracts away workers’ subjectivities by reducing them to anonymous packets of time that can be activated on demand. This Biology professor from Venezuela used this imposed abstraction and anonymisation to her own advantage, but we might want to ask: why did she need to? Why should an incredibly smart woman with a PhD earn less due to her nationality and gender? This is what I meant previously in relation to the question of what has changed or not in the care labour market after its migration online. That is, it remains problematically attached to the same logic of a colonial and patriarchal model by which the labour of some workers is devalued because of their gender, ethnicity and race.

EL: Do humans have an ethical responsibility to care for networked non-humans and is it a mutual responsibility? What might this look like?

EGP: My research is trying to reframe the question of ethical responsibility towards machines – or networked non-humans – by focusing instead on the anonymous infrastructure of underpaid human workers that is sustaining automation: we might call this an invisible socio-technical assemblage. For example, consider the case of the ‘Invisible Boyfriend’ I mentioned earlier. The company uses underpaid workers as invisible proxies for an artificial intelligence system that might, at some point in the future, simulate emotional conversations. I found another example of the same dynamics when I was working on my latest project – Cleaning Emotional Data (2020) – in which I documented the human outsourced labour involved in categorising massive quantities of visual data used to train emotion recognition algorithms. This is all to say that I believe the question of human empathy towards machines is an important one, but mainly because it allows us to pose an even more urgent question: do we have an ethical responsibility to consider and address the working conditions of the labourers who are rendered invisible by this techno-fantasy of automation? I think we do.

EL: Within the proposition text you signalled a move to isolate a certain segment within your larger series, Technologies of Care. In particular you decided to develop a stand-alone conversation with the ‘Invisible Boyfriend’. Could you elaborate on the significance of expanding this segment further?

EGP: As soon as I finished Technologies of Care in 2016, I realised that I wanted to expand the ‘Invisible Boyfriend’ fragment as a stand-alone video piece, because it seems to speak more directly to the inequalities already embedded within autonomous artificial intelligence systems. The current debate regarding artificial intelligence, as I mentioned before, seems to consistently overlook the human infrastructure that enables it. The salient concern seems to be the exclusion of the human from the loop of automation – paired with a fear of the loss of some supposedly inherently human characteristics in automatic systems, such as emotional intelligence and empathy. But what we might fail to recognise is that not all humans are excluded from the procedures of automation. Indeed, so many workers are so deeply imbricated in the operations of the machines that their labour becomes subsumed and invisible.

EL: In the proposition text, you mention re-editing and reformatting the conversation. You also mention ‘including fragments that did not fit in the previous work’. What within this three-month-long text exchange stands out the most to you, such that it inspired you to revisit the piece?

EGP: In Technologies of Care (2016), I had to condense a three-month-long conversation into a segment lasting only a couple of minutes, so I had to cut extensively. One aspect I would like to recover is that of gender performativity. The majority of the freelance writers employed by the company are women, regardless of whether or not the client built the profile of the virtual boyfriend to be a male. Also, no option apart from the normative male/female binary is given. The resulting labour is, therefore, effaced care work, which demands that workers participate in further effacing themselves as subjects while performing as a categorisable gender. If I were to re-edit the piece, I would give more space to this topic.

Above Image: Elisa Giardina Papa, Cleaning Emotional Data, 2020, video installation; three HD videos, colour, sound, 18 min. embroidered textiles, variable dimensions. Exhibition view of Algotaylorism curated by Aude Launay, Kunsthalle Mulhouse, France, 2020. Textile pieces developed in collaboration with Michael Graham [@mikegrapes] of Savant Studios (Brooklyn, NY). Photo : Sébastien Bozon. ©️image courtesy of the artist

References

Articles

Mackinnon, Lee. “Love Machines and the Tinder Bot Bildungsroman.” e-flux Journal, 74, (2016).

Staal, Jonas. “Comrades in Deep Future.” e-flux Journal, 201, (2019).

Poem

Brautigan, Richard. All Watched Over By Machines Of Loving Grace, 1967.

Books

Non-Fiction

Braidotti, Rosi. Posthuman, Polity, 2013.

Fisher, Mark. The Weird and the Eerie, Repeater, 2017.

Goldsmith, Kenneth, Wasting Time on the Internet, Harper Perennial. 2016

Hayles, N. Katherine. Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive Nonconscious, University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Lovelock, James. Novacene: The Coming Age of Hyperintelligence, Penguin Books, 2019

Phillips, Kaitlin Ugolik. The Future of Feeling: Building Empathy in a Tech-Obsessed World, Little A, 2020

Puig de la Bellacasa, María. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds, University Of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Rai, Amit S. Jugaad Time: Ecologies of Everyday Hacking in India (ANIMA: Critical Race Studies Otherwise), 2019.

Fiction

Asimov, Isaac. I, Robot . Greenwich, Conn: Fawcett Publications, 1950.

Butler, Octavia E. The Parable of the Sower, Headline, 2019.

Dick, Philip K. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? London: Gollancz, 2011.

Gibson, William. Neuromancer. New York: Ace Science Fiction Books, 1984.

Films

Ex Machina. Dir Alex Garland. Universal Pictures, 2014, Film.

Ghost in the shell. Dir Mamoru Oshii, Manga Entertainment, 1995, Film.

Her, Dir Spike Jonze, Sony Pictures Releasing, 2013, Film.

The Animatrix. Dir Shinichirō Watanabe, Yoshiaki Kawajiri, Koji Morimoto, Takeshi Koike, Peter Chung, Mahiro Maeda, Andrew R. Jones, Warner Home Video, 2003. Film.

Documentaries

Shenzhen: The Silicon Valley of Hardware, Future Cities, Dir. Jim Demuth, WIRED, 2016, Documentary.

Above Image: This image is for illustrative purposes only

Supported By

This project is the result of the combined efforts of many collaborators. The Empathy Loading curatorial team would like to acknowledge and thank:

The project’s collaborators who have contributed artworks, research and expertise:

Amina Abbas-Nazari

Friendred

Elisa Giardina Papa

Studio Hyte

Vishal Kumaraswamy

Marie-Eve Levasseur

Zarina Muhammad

Allison Parrish

Curating Contemporary Art RCA staff, for their continuous academic support and encouragement during the entirety of our Graduate Project, in particular:

Kelly Large

Victoria Walsh

Our partner, Furtherfield, for their commitment to the project and the guidance they have provided, in particular:

Ruth Catlow

Charlotte Frost

Marc Garrett

To everyone who influenced the curatorial team’s thinking in the development of the project and generously shared their time, knowledge and experiences: thank you!